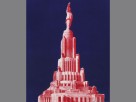

Mikhail Karasik: THE USSR's TOWER OF BABEL

Event Venue:

Harriman Institute of Columbia UniversityHarriman Atrium 420 West 118th Street, 12th Floor

New York, NY

Event Date:

Opening Reception: Tuesday, November 14, 2017 | 6:00 – 8:00 pmExhibit on display from November 13, 2017 until January 11, 2018

Curator: Regina Khidekel

The Exhibition opening:

Watch Regina Khidekel's opening remarks at Mikhail Karasik: THE USSR's TOWER OF BABEL exhibition via YouTube

The opening of the exhibition of Mikhail Karasik was held at a huge gathering of absolutely wonderful people - friends, admirers, students. specialists ... generous treats did not go unheeded either. Introduction by Maria Ratanova, Columbia University.

On the screen, as a background, the video about the sculptor Sergei Merkurov, who worked in his studio in 1938 on the models of the Palace and sculpture of Lenin, played silently, presenting an additional element of temporary authenticity in the interpretation of the event. (Merkurov – Palace of the Soviets) via YouTube

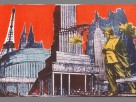

THE USSR’s TOWER OF BABEL, an exhibit of lithographs by Mikhail Karasik, is dedicated to the centenary of 1917--a year filled with world-changing events. 1917 saw the arrest of suffragists picketing the U.S. White House, and the historic Balfour Declaration. But, among these landmark events, the two Russian revolutions undoubtedly bore the greatest consequences.

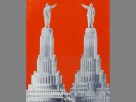

Karasik selected the construction of the Palace of Soviets--the most grandiose building of the 1930s--as the symbol of victorious socialism. Over time, this giant construction in the center of Moscow, has become a myth that continues to attract the attention of historians, culturologists, and architects.

The exhibition consists of 22 works from two albums of lithographs: "The Palace of Soviets. Design Competition" (2006) and "The USSR’s Tower of Babel" (2010). For Mikhail Karasik, the Palace of Soviets is more than an architectural project, it is a symbol of utopia, the symbol of a country dissolved. The artist worked on these albums for more than a decade.

According to Mikhail Karasik, along with hundreds of thousands of tonnes of steel and concrete, there were two ideas that went into the making of the foundations for the Palace of Soviets: the subconscious complex that the Bolsheviks had developed during the first years of Soviet rule as a result of their lack of creative activity; and the religious/materialist bent of their new faith, which required that socialism should be embodied in something supernatural, but objective – in something that could be seen and touched rather than simply accepted as a matter of belief (like the establishment of a new social order on Earth, announced from the Party pulpit at the Extraordinary Congress of Soviets in 1936). The Bolshevik’s religious consciousness required that real proof be presented. Now, it might seem that such proof might have been found in the cities and factories built during the first and second five-year plans, but these cities and factories, as a consequence of the industrialization of the Soviet Union, were not a goal, but merely the means by which the New Socialist House was to be built.

The first prototype for the ‘Principal Building in the Country’ was Vladimir Tatlin’s famous Tower of the Third International, which had been designed to be used for Comintern meetings and was to be constructed, according to its author, “from iron, glass, and revolution.” This was an impossible project to realize, but the idea which it embodied did not die with it.

The Bolsheviks returned to the idea of building a palace in 1931. A national competition was announced. There were 160 entries, of which 24 were by foreign architects (eleven from the USA; five from Germany; three from France; two from the Netherlands; and one each from Italy, Switzerland, and Estonia). Participants in the competition included all the leading Soviet architects and architecture offices of the day, as well as famous Western architects such as Hans Poelzig, Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Le Corbusier, Hector Hamilton, Alfred Kastner, and Oscar Stonarov. The competition turned out to be a turning point for Soviet architecture. This meant that the architectural competition to design the Palace of Soviets produced not just the best design for the building, but also a new architectural doctrine, which would later come to be called ‘Stalinist architecture’, ‘Stalinist Empire Style’, ‘Stalinist Neoclassicism’ or ‘Stalinist Gothic’. The essence of this architecture was the mortification of architectural thought.

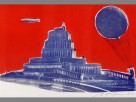

On May 10th 1933, after the third round of the competition, the Council for Construction adopted as the basis for the project a design by architect Boris Iofan. This specified a 3-tier tower accentuated by dynamic, vertical rib-like pylons and topped by a statue of the ‘Liberated Proletarian’. Stalin gave orders that the building should be topped by a sculpture of Lenin. In the process the number of tiers was increased to five and the building’s total height was now to be 415 metres (seven metres higher than the Empire State Building). The sculptural competition was won by Sergey Merkurov, yet another favourite of the Leader: “At the command of Comrade I.V. Stalin the sculptor depicted Lenin with arm stretched out in front, in a pose depicting a call to action. The statue of Lenin (100 metres high) crowning the Palace of the Soviets will be the largest sculpture in the world” (Dvorets Sovetov, Moscow, 1939).

Mikhail Karasik was born in Leningrad in 1953. Graduated from the graphic art faculty of the Leningrad State Herzen Pedagogical Institute. Fields of activity: easel graphic art, books, posters, objets d’art; works mainly in the lithography technique. Member of the Artists’ Union. Has participated in exhibitions since 1978. Since 1987 Mikhail Karasik has created more than 100 artist’s books and objet d’art. Karasik is a regular participant in international art salons. Lives and works in St Petersburg.

The artist is one of the originators, ideologists and popularizers of the artist’s book in Russia; a publisher of books and catalogues, the author of numerous articles on the artist’s book and the early twentieth-century Russian avant-garde, as well as albums studying the Soviet photobook history; one of the organizers of the Kharms Festivals in St Petersburg (1995–2005), curator of the numerous exhibition projects. Since 1987 Karasik has created more than 100 artist’s books and objet d’art. Mikhail Karasik’s publishing house, M.K. Publishers, is a regular participant in international art salons.

Major solo exhibitions: Gutenberg-Museum, Mainz, 1993; Central House of Artists, Moscow, 1993; Cabinet des estampes du Musée d’art et d’histoire, Genève, 1994; Anna Akhmatova Museum at the Fountain House, St Petersburg, 1995; Yaroslavl Art Museum, 1995; Saxon State Library, Dresden, 1998; Art Institute of Chicago, 1998, 2010; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, 2001; State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, 2003; Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts, Ekaterinburg, 2004; Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen, 2010; Bibliotheca Wittockiana, Brussels, 2011; Museum of the St Petersburg Avant-garde (Matiushin House), St Petersburg, 2011; The Novy Muzei [New Museum] of contemporary art, St Petersburg, 2012; Russian National Library, St Petersburg, 2012; Shchusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow, 2013; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2015; Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow, 2016

Works by Mikhail Karasik in public collections: Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, State Tretyakov Gallery, Shchusev State Museum of Architecture and Russian State Library in Moscow; State Russian Museum, State Hermitage Museum and Russian National Library in St Petersburg; The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Museum of Modern Art Library in New York; Art Institute of Chicago; Library of Congress, Washington; Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, New Jersey; The Getty Research Institute and Institute of Modern Russian Culture in Los Angeles; Victoria and Albert Museum and British Library in London; Musée National d’Art Moderne / Centre Pompidou and Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven; Gutenberg-Museum, Mainz; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München; Cabinet d’arts graphiques du Musée d'art et d'histoire, Genève and others.

Publications: Paradnaya kniga strany sovetov [The Paradnaya Kniga of the Country of Soviets: Great Stalinist Photographic Books], Moscow, 2007; Udarnaya kniga sovetskoy detvory [The Udarnaya Kniga for Soviet Children: Photographic illustration and photomontage in books for children and youths in the 1920s and 30s], Moscow, 2010; The Soviet Photobook 1920–1941, Steidl, 2015; The Photobook in the USSR (St Petersburg, 2015); Iskusstvo ubezhdat, Moscow, 2016.

EVENT LISTINGS & PRESS

Harriman Institute commemorates Russian artist Mikhail Karasik in new exhibit by Gia Kim (Nov 18, 2017), Columbia Spectator

Harriman Institute at Columbia University

H-SHERA (Humanities and Social Sciences Online)

RACC’s programs and events are made possible in part by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and Cojeco.